Janet Hamlin has been covering Guantánamo for seven years, making more than 25 trips to the prison. Her work provides a rare and unique view into the controversial military commissions proceedings - and the only view of the small number of detainees charged with crimes (of the 164 prisoners that remain at Guantánamo, only six face formal charges). Sketching Guantánamo, a compilation of her work with accompanying essays, just hit the shelves. The artist exchanged ideas and answered questions last week over the phone and Gmail Chat conversations.

Michael Bronner: The book is just out. How's it doing? What feedback have you had so far?

Janet Hamlin: So far it's been well received. It's just come out so we'll see how that goes. There have been mostly positive reviews, and one that was a little critical that I had not taken a political stance, but my goal is to let the viewer/reader make his or her own opinions based on what I've sketched.

MB: Understood. But there must have been an inspiration to assemble the images and essays in one volume...

JH: After the 3rd year of sketching it had become apparent that I had the unique sequential perspective of these trials gathered visually and many friends and colleagues asked if I'd be doing a book. The idea germinated, and here we are seven years later. It was a lot of work to figure out how to organize, fact check, etc., and with the help of many it's come to fruition. I am proud of how it's turned out. I am also pleased that there are other contributors featured in the book - the piece by Salim Hamdan and his translator about what the experience was like from his perspective; Carol Rosenberg's opener; Michelle Shephard's chapter on Omar Khadr; and others.

MB: Carol Rosenberg is the Miami Herald reporter who has covered Guantánamo more than any other. Michelle Shephard, also very dedicated to reporting the story, is the author of a book on the case of Canadian former detainee Omar Khadr. It's the third contributor you named that's a real surprise: Salim Hamdan was Osama bin Ladin’s driver, a former detainee from Yemen released in 2008 after six years of captivity. You solicited first-person insights from him. How did that come about?

JH: Michelle Shephard put me in touch with Salim Hamdan’s interpreter, Charles Schmitz, who was able to forward my sketch images to Hamdan for response as to how he felt in each scene. Here is his response to the first sketch I did of him in the courtroom:

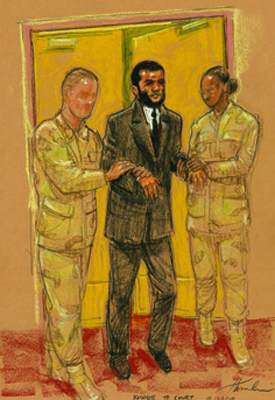

This was the first time I was in court and the first time I saw the motions and the judge and lawyers from each side like I had seen in the movies and I didn’t understand anything about the law and the court procedures. I wondered whether the trial would be fair or only what the American government wanted. They weren’t using civilian law or military law and they made up a new law that doesn’t offer anything in favor of the prisoner...

Salim Ahmed Hamdan at his military commission in July 2008. He was found guilty of providing material support to al Qaeda but was acquitted of terrorism charges.

JH: I wanted to provide a unique perspective from within - that of a detainee on trial - and I was able to get access to Hamdan. His was the first case tried that did not end up in a plea deal, and big news.

MB: You have a perspective on Guantánamo that spans seven years, longer than all but a couple of reporters. Do you remember your thoughts upon getting that first assignment to go to Guantánamo?

JH: The Associated Press needed to send a sketch artist to draw Canadian detainee Omar Khadr, who was 19 at the time. Going to Gitmo was foreign, and somewhat daunting. I had no idea what to expect. There were many rules I was concerned about – not being able to draw the detainee's face, for instance. That rule was lifted the following year with David Hicks [an Australian detainee, who has since been released].

MB: I want to ask you in detail about the rules. But first I wanted to step back and ask you to give us a sense of the history of sketch art in legal settings. We’ve become used to cameras in courtrooms – photographs of nearly everything that transpires, really, from CTV to Youtube and iPhone images. Where does courtroom sketch art exist in the order of evolution?

JH: It's one of the last vestiges of old-time image capturing. An observer at Gitmo brought in some printouts once of engravings from at least 200 years ago. Several courts still have sketch artists, but as you mention, more and more we are seeing cameras in the courtrooms. There are only about five artists in NY that cover the courts these days.

MB: Do you consider yourself more an artist? A journalist? What is the interplay between the two callings? Interpretation, impression, objectivity - there must be times when they clash…?

JH: One of the things the art director at AP asked is that I keep things as true to what I see as possible – not to move people around, but to sketch them where they are. To be a “visual journalist,” in a way. But of course there are times when it's very difficult to be objective, and I do have to edit and interpret. The whole time I'm hoping to bring back a compelling image that is as true to what happened as possible.

JH: Sometimes the editing is part of the deal there, given the strict rules: no doors can be drawn, for example. Guards, anonymous witnesses, various security or other personnel cannot be sketched. Depending on the judge, even an outline of a military panel (the jury) cannot be sketched, so I ended up drawing huge blue tabs with numbers to indicate that there were jury members sitting there, as a visual compromise.

MB: Guantánamo is a place where the rules are a moving target. How have they evolved (or devolved, as the case may be at times) in terms of your work?

JH: There's a huge rotation going on all the time. Every six months there is a new crew of PAOs [public affairs officers who escort members of the press] who have been trained, yet interpret the rules differently. So sometimes reporters can bring in wire notebooks, other times not, for example. For me, I could bring in stadium glasses to help with the distant view (Court 2, the maximum-security courtroom, is a challenging venue, drawing from behind soundproof glass in back of courtroom). After three years of using the glasses to see a bit better, I was told no more stadium glasses.

The author, with the tools of her trade, being escorted on the base.

JH: Sometimes I am asked to show a passport to get into court, other times not, so I always carry a passport (even though I have a media badge). One time I was told a detainee did not want his sketches shown so was told by the court security officer, who has to sign off on all sketches before they go out (the same person that can censor the sound from the courtroom broadcast into the press booth), that I could not have my sketches back unless I blacked the detainee out. Instead, I remained in the court area and asked to have the military spokesperson help me by making calls from court until we had a valid reason for such censorship. It took us 4 hours, but we got the right to move the sketches.

MB: What's so striking about your book is that it covers so many years. You actually see some of the detainees change physically – in the case of Omar Khadr, from a boy into a man – in your images. Are there cases that have affected you more than others?

JH: Omar's hearings and trial were the most comprehensive, and there were many moving moments during those years. He really did grow from a boy to a man in those years. There were so many moments in his trial – a guard who took pity on him; the video of him as a child making a road bomb; the widow of the soldier killed by the grenade he plead guilty to throwing; his apology to her...The sketches in the book are the best explainers. In a nutshell, when I first drew Omar he was like a lanky puppy. The following year, an unhappy young man with untruly hair, quiet and withdrawn. The year after that he was in a white uniform (designating compliance) and engaged in the court happenings. He dressed in a suit when the trial itself began and apologized to the widow of the soldier killed during the battle in which he was captured. It was a very moving moment.

Canadian Omar Ahmed Khadr, captured in Afghanistan at age 15, was one of the youngest imprisoned at Guantánamo.

Khadr accepted a plea agreement to murder in violation of the law of war and providing material support for terrorism. He was transfered to Canadian custody after more than ten years at Guantánamo.

JH: Of course, the hearings involving the 9/11 accused - Khalid Sheikh Mohammad's declaration of guilt, for example - were very affecting. I was in Brooklyn when 9/11 happened and lived that day, so to see the man who claims to have masterminded that was a powerful experience.

Equally so to meet the victims’ family members who come to the court to share their stories and sit beside us in the media viewing room.

MB: I understand you specifically displeased Khalid Sheikh Mohammad with one of your sketches...

JH: Yes. The first time I drew Khalid Sheikh Mohammad, he did not like how I drew his nose, so the sketch was held on premises at the courtroom until I could print out a reference photograph, return to the court, alter the nose until it matched the printout, and then the security officer signed off so the sketch could move.

Given the restrictions, when I draw close-ups of faces, the best views are actually from an entirely different building up the hill from the court. There they have monitors statically positioned with split-screen views of each detainee face-forward. Ironically, I draw better sketches from those. I'd pitched wearing noise cancelling headphones with two security agents bookending me while sketching so that I could get into the actual courtroom for a better view like we do here in New York courts, but I don't have the security clearance. The separate room with the monitors was the military's compromise.

Hamlin took advantage of a rare moment when KSM turned to face the back of the court, capturing this image.

MB: The KSM sketch was the first opportunity for the world to “see” the face of the accused mastermind of 9/11 since his capture in March 2003 (we all remember the photograph of the unshaven, sweaty, about-to-be-rendered accused terrorist that the US government released). His lawyers were obviously aware of the potential impact of your sketch. Do all detainees have the right to review the images?

JH: It had never happened before, but this time for some reason the security officer felt it should be shown to KSM's lawyers before he'd okay it. And then I saw through the glass KSM looking at it and shaking his head, clearly displeased. After that, there were no other times that the detainees shown sketches for approval until Majid Khan [a Pakistani detainee accused of conspiring with Khalid Sheikh Mohammed in plotting terrorist attacks]. The court security officer claimed that Majid had the right to not allow my sketches to be released and used by the media, but did not have anything in writing to substantiate his claim. I did not want to leave the court until I could leave with my sketches. It resulted in a standoff. A commander who assists the media had to come to the courtroom and make phone calls for several hours to verify if Majid Khad did indeed have the right to not allow sketches to go out. Four hours and several phone calls from the court later, we got the approval to keep the sketches and allow media to show them. Since then, there has not been a request to show detainees sketches for approval.

MB: The book includes more than just the courtroom sketches – there several scenes from Guantánamo outside the courtroom. Are there a few you can describe that were particularly significant for you to include?

JH: Sketches of the camps (the Pentagon's term for the prison areas) are no longer allowed during military commission (the trials and hearings), so having those sketches is important.

Ibrahim Ahmed Mahmoud al Qosi admitted to being Osama bin Laden's cook and pleaded guilty to conspiracy. He was sent home to Sudan after more than ten years at Guantánamo.

MB: Seven years and more than 25 trips later, you continue to go to Guantánamo as a freelancer – in other words, by choice. How long do you see yourself staying with the story?

JH: I hope to stay with it until the 9/11 trial has completed.

MB: Given all the restrictions you’ve worked under; the constant escort, oversight and monitoring you describe in the book, and that all journalists are subject to; all the difficulties associated with even getting to and from the prison – I’m left with a sense that the very act of producing a beautiful, insightful, accessible volume providing a window into the proceedings in and of itself constitutes an act of defiance. Am I wrong…?

JH: In fact, many in the military were very pleased to know I was putting a book together of all the sketches. While it’s true I have to jump hoops getting to and from Gitmo, and put up with changing rules and challenges, I try not to take these restrictions personally.