(translated from the French by Armelle English)

I have been traveling widely in the Ukrainian Donbass, the contested region of Eastern Ukraine, since the day after the Minsk agreements, which were supposed to seal the truce between the fighting parties in Eastern Ukraine. Having covered numerous wars in the mid 1990s (Chechnya, Serbia, Iraq, Syria, Afghanistan), I have never been confronted with such media-centric hysteria as I’ve experienced here, which makes it extremely difficult to figure out what’s going on.

My Ukrainian colleagues, with a few rare exceptions, have found it impossible – for fear of violent retaliation – to report from the same city I am writing you from, Donetsk. Strikingly, quite the opposite is true for Russian journalists, particularly the powerful television teams, who enjoy complete – almost exclusive – access to the civil and military representatives of the two self-proclaimed “People’s Republics,” Donetsk and Luhansk, as well as their protection.

Between the two stand Western journalists like me who, theoretically, have access to both sides. The reality, however, is that Western journalists are fairly welcome on the “pro-Ukrainian” side, but not so welcome on the “pro-Russian.” In each "camp," preconceptions and stereotypes about the other side abound, including among some journalists, which I deplore. The fact that I am a Russian speaker gives me access to the “pro-Russian” camp, although before speaking to me, my various interlocutors exhaustingly weigh the various hypothetical advantages and disadvantages of a possible discussion with me and try to make sure that I will re-transcribe “the truth.” I am weary of having to repeat to everyone that “the truth” in journalism, as they conceive it, does not exist.

“Truce? What truce?”

Regardless of whether I’m in the metropolis of Donetsk or further east in Luhansk, it’s hard to find anyone who will express trust in the document signed on September 5th in Minsk outlining the terms by which the warring factions are expected to cease hostilities. The decision of the Verkhovna Rada (Ukrainian parliament) on September 16th - providing for the implementation of the “peace plan” promising greater autonomy and outlining terms of an amnesty for participants in the fighting in Donetsk and Luhansk - has not changed the general mood in any way: In Eastern Ukraine, in the “ATO zone” [“anti-terrorist operation zone”] where the fratricidal war has played out among Ukrainians, distrust in the central power in Kiev has never been stronger.

“Kiev may announce what it wants to the world, but we here in Luhansk are still in shock from the summer we have spent in our basements waiting for the fighting to stop and praying we will get through this,” explained a palpably exhausted Yuri Yurov, editor in chief of “Twenty First Century”, the local newspaper (which has become “Republican,” he insists, and began circulation again only on September 17th). The gift of autonomy from Kiev to the two separatist regions has not in any way pleased the secessionist authorities, who consider the decisions first and foremost as palliatives for the Ukrainian population from which they have excluded themselves.

Of the Eastern cities engulfed in the summer’s violent fighting between the Ukrainian Army (assisted by battalions of volunteers) and local separatist forces supported by the Russian military, Luhansk has suffered the most. The city celebrated on the 14th of September, despite the sad circumstances, and the center of the city is again connected to the electrical network, which the population is pleased with. However, in front of the oblast’s administrative building, which has become the headquarters of the self-proclaimed People’s Republic, many gather to complain about the confusing nature of the situation. A woman cries while recalling the fate of her son, who is still being held “hostage” by unknown militants, a situation the new representatives of the administration seem to care very little about. Another woman complains that, despite the opening of some schools on September 1st, children are not taught in normal conditions, since “most teachers have left, just as doctors have left hospitals, for that matter.” The most flagrant and recurring issue pertains to pensions, which the new People’s Republic’s administration promises to pay “in the near future.”

“Practically all our banks are closed. To withdraw cash from our bank accounts, one has to venture out of the ATO zone at one’s own risk, which seems beyond the pale, does it not?” says Vadim, an unemployed miner about to spend hours on a Kramatorsk-bound bus to a Ukrainian controlled area south of Slavyansk.

In the prevailing chaos, rumors of all kinds proliferate, for example one on the forced nationalization of local businesses. Yuri Yurov, the local editor, provides some clarification: “This law, useful, will be voted in as quickly as possible and will deal with large metallurgy companies, mines, public banks, postal services, as well as the railroad network.” As for properties that were seized, often by force, they will theoretically be returned to their owners if they show official proof of ownership, he said.

Geographically closer to Russia than the region of Donetsk, where the fighting is still raging (notably at the airport located only a few kilometers away from the city center), there is no doubt that in Luhansk all eyes are on Moscow. However, no real reassurance has emerged as of yet. “First, we are expecting a commitment from Moscow – moral support, of course, for our cause, but also a different type of support,” Yurov adds. By “a different type of support,” he means military support, “if it becomes necessary.”

About 200 kilometers west, in Donetsk, the decline of the Ukrainian forces at the end of the summer has automatically been associated with the military and logistical aid that came from Russia. However, worn out from privation and anxious about the difficulties ahead in terms of supplies for the winter (lines at gas stations, which also provide propane gas for vehicles, are testament to huge shortages, and pharmacies and hospitals are no longer adequately stocked), the population of the Donbass’ central metropolis is not naive: “Why hasn’t what happened in Crimea happened here?” is a question heard in every conversation. Disappointed, angry, depressed and anxious, the people of Donetsk are awaiting better days, while no longer knowing where to turn to in the absence of a clear and efficient power center. “That is why we, the military, are here,” explains Mongol, a separatist commander active since the beginning of the hostilities. He attempts to hide his disdain for the Minsk agreement, which he considers “treason.”

“For the time being, the people must rely on us. Victory is near,” he says.

After more than three thousand deaths and hundreds of thousands of civilians displaced (both to Russia and the western regions of Ukraine), could the Ukrainian civil war really be over? Many hope so; they hope that the ceasefire signed in Minsk and the decisions initiated by Rada will serve as a pillar for resolving the problem. In the area where the fighting occurred, however, the people – full of resentment and divided – remain in doubt.

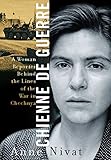

Anne Nivat, a Warscapes Advisory Board member, is an award-winning war reporter and author. She covered the Chechen war for the French daily Libération and was based in Moscow for ten years until 2005. Nivat has written pieces for The New York Times, The Washington Post and the International Herald Tribune, and has appeared on NPR's Fresh Air, The Connection, and PBS's News Hour. She holds a doctorate in political science from Institut d'Etudes Politiques de Paris, and was a Fulbright Fellow at the Davis Center for Russian Studies at Harvard University. For her first book, Chienne de Guerre: A Woman Reporter Behind the Lines of the War in Chechnya, she disguised herself as a Chechen woman and traveled to the war-torn region despite a Russian ban on journalists. Her books include The View from the Vysotka; The Wake of War; Encounters with the people of Iraq and Afghanistan; and The Fog of War. Nivat is based in Paris and travels extensively covering Iraq, Syria, Jordan, Pakistan, Afghanistan and Central Asia.