Okwui Enwezor described the ephemera of Africa that arrived at European docks as “strange cargo”: As it was unloaded from ship to warehouse by longshoremen; as it was bid on, sold, and displayed in wealthy homes; lost and rediscovered; each object shaped European visions of Africa. "Africa," as we imagine it now, was shaped by that strange cargo. Later, in his essay in the January 1996 issue of frieze, Enwezor asked, “Why do we never consider the achievements of those artists who at great professional cost and individual isolation have not only transcended but have equally transfigured the borders constituting the notion of Africanity?” South African artist Jane Alexander’s work, now positioned throughout the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in Manhattan’s Morningside Heights neighborhood, is part of the tradition of Africa’s strange cargo, but it is freight that – possibly at the cost of easy audience engagement, and curators’ comprehension – certainly transfigures notions of Africanity. Hers are not the masks and pretty pictures of African bodies - the smiling faces (or incongruous bodies) from the Dark Continent. Instead, her figures make the viewer reflect on the grotesque triumphalism inherent in looking away in the face of suffering - on the cost of participating in, and benefiting from, great sweeps of violence, and the solitude of bearing the brunt of marching empires that see nothing of your existence.

Okwui Enwezor described the ephemera of Africa that arrived at European docks as “strange cargo”: As it was unloaded from ship to warehouse by longshoremen; as it was bid on, sold, and displayed in wealthy homes; lost and rediscovered; each object shaped European visions of Africa. "Africa," as we imagine it now, was shaped by that strange cargo. Later, in his essay in the January 1996 issue of frieze, Enwezor asked, “Why do we never consider the achievements of those artists who at great professional cost and individual isolation have not only transcended but have equally transfigured the borders constituting the notion of Africanity?” South African artist Jane Alexander’s work, now positioned throughout the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in Manhattan’s Morningside Heights neighborhood, is part of the tradition of Africa’s strange cargo, but it is freight that – possibly at the cost of easy audience engagement, and curators’ comprehension – certainly transfigures notions of Africanity. Hers are not the masks and pretty pictures of African bodies - the smiling faces (or incongruous bodies) from the Dark Continent. Instead, her figures make the viewer reflect on the grotesque triumphalism inherent in looking away in the face of suffering - on the cost of participating in, and benefiting from, great sweeps of violence, and the solitude of bearing the brunt of marching empires that see nothing of your existence.

Almost nine years ago, in July 2004, I made my way to the South African National Gallery in Cape Town to see a show celebrating “A Decade of Democracy.” On the front of the museum’s dazzling white walls, the laughing, joyous photographic image of Tracey Rose’s “The Kiss” – an homage to, and a parody of, August Rodin’s marble perfection – greeted visitors. Rose is captured in all her carnality, corporeal imperfections intact, seated on the lap of her art dealer: It’s an image that would catch one’s eye anywhere, first because both people are beautiful, nude and are in the midst of a moment of delightful intimacy, but also because of the freedom, spontaneity and love between them. In South Africa, of course, a seemingly white woman cavorting on a black man’s lap has added layers of significance. But these appearances of ‘racial’ identity are deceptive; although the woman in this monochromatic image, Rose, seems to be pale-skinned, she would not have been classified ‘white’ during apartheid, and much of her work makes reference to such complexities. Given that this was the frontispiece to an exhibit marking ten years out from the yoke of Afrikaner moral strictures, I entered the building expecting art that looked forward and outward: less introspection, and more unrestrained joy.

But inside, the story was far more complex. There, I had my first introduction to Jane Alexander’s work, Butcher Boys: Three seated man/animals oddly reminiscent of an upside-down Pan - that delightful, sensuous creature with the lower body of a hoofed animal from Greek mythology. But Alexander’s animalistic men exhibit none of the voluptuous sexuality of Pan. The head of each of Alexander’s Boys is a different type of horned animal, and the bodies are lean and hungry, with musculature, ribs, and spine showing. They sit in a row on a low bench, their long bodies a little hunched over, their legs in the pose of men who are waiting the long wait for some mode of unreliable public transport to take them away. In certain places, each Boy’s ribcage parts in a black gash, revealing spinal cord through bone-coloured flesh; a similar gash is repeated along the front, hinting of the passage of an autopsy knife. The skin on each horned head is drawn so sparely over bone that the faces appear nearly skull-like; ears appear to be lopped off, and where the snout should extend to the mouth, another truncation. Whatever appendages there might have been beyond the nose have been either hacked or sealed off. These Butcher Boys are not in conversation with one another, with the world, or with the viewer. Each deaf-mute head is turned in a different direction: the glass eyes – opaque, black, and curiously luminescent – look away and out. I remember standing by those sets of oblique eyes thinking, "He sees me. He sees through me. He sees me not at all." It would be foolhardy to ask such men to hear, converse, internalise anything at all.

Alexander’s work does not operate on the pivot of amnesia, even at a moment of state-mandated celebration. Celebrations look to futures untainted by troubling pasts. They ask us to live in a decontextualised present. Her work is a meditation on what happens to such bodies, to such heads, to such souls. To see these man-beasts, seated thus on a bench, is to be stilled – stunned – by the macabre inherent in the ordinary bystander. Butcher Boys is an unapologetic meditation on the animal nature of a collective body that disengaged from its political and social present: of those who waited, as if for a bus or a long-delayed plane, for some unnamed future – unspeaking, unhearing, eyes deliberately unfocused on culpability or responsibility. It would be a cliché to say, “When you butcher without awareness, or consume the spoils of such butchery without honouring the sacrifice, you become animal.” But that understanding is inherently present, without having to be overtly stated.

Since then, I’ve seen Alexander’s work on a few other occasions, and each time, I walk away having experienced something close to transfiguration – as if what I consumed has entered my body, changing the very way I "be" in this world.

* * *

When I heard that Jane Alexander’s work would be shown in the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, I wondered how the work I always associated with South Africa would translate here, in an April scattered with springtime’s hopeful crocuses and lily of the Valley. As I travelled down to the city, upstate apple blossoms – their lives of delicate abundance lasting barely a week – were almost ready to shed petals on cars parked below. On the highway, the odd car was covered in white or pink disks: sequinned emissaries, travelling with a message of transformation.

Jane Alexander, The Sacrifices of God are a troubled spirit (Photograph by Mario Todeschini). Courtesy of the Museum for African Art.

The invitation to the opening of the show, “Surveys (from the Cape of Good Hope),” organized by the Museum for African Art in Manhattan in collaboration with the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, promised the first major North American survey of tableaux, sculptures, and photomontages by Alexander. The image on the invitation is itself a montage: It shows “The Sacrifices of God are a troubled spirit,” Alexander’s installation in the "All Souls" altar of the Cathedral of St John the Divine for the exhibition Personal Affects in 2004, a group exhibition also arranged by the Museum for African Art. Alexander’s amputated human-animal figures pose among rusting sickles and blood-red rubber gloves, all positioned in front of a triptych depicting the ascension of Jesus. Haloed kings, apostles, sinners, and angels surround the King of Kings, who looks on at the scene with kindly benevolence. The ornate gold frame made me think of the Baroque penchant for hiding violence under gilded beauty.

Alexander’s work arrived in the Cathedral of St. John the Divine of the Episcopal Diocese of New York during the same fortnight as excerpts from a new memoir by Guantanamo Bay detainee Mohamedou Ould Slahi were released on Slate magazine. Before I stepped into the church, I sat outside, in the blooming gardens adjacent to the church, reading. Three peacocks – Phil, Jim, and Harry – strutted around the tulip beds. In a city that barely had space for a window planter, these rambling flower beds – a cross between an English garden, with hints of Dutch, and my grandmother’s hilltop home in Sri Lanka where peacocks meander through the coffee trees – sit like a jewelled necklace on a bare body. The towering cathedral walls, the cornerstone of which was laid in 1892, mirror the longings of the first great waves of European immigrants to the city; 1892 was the year that Ellis Island, conduit to the hungry and the penniless of Europe, opened. There, strengthened by the walls enclosing the seven Chapels of the Tongues commemorating the major immigrant groups pouring into and building the city, I sat and read an excerpt of Slahi’s memoirs, thinking of the hundred men on hunger strike, and the many who are being force-fed right now, men who describe the unspeakable pain meted to their bodies in the name of feeding them, in the name of sustaining and caring for their bodies. In Part One, “Endless Interrogations”, Slahi writes,

There was a very old Afghani fellow, who reportedly was arrested to turn over his son. The guy was mentally sick; he could not stop talking because he didn’t know where he was, nor why. But the guards kept dutifully hanging him. It was so pitiful; one day one of the guards threw him on his face, and he was crying like a baby.

I think about what it would be like for my father – a man in his seventies, diminished by several strokes – to be thusly hung, and flung on his face, to be damaged by young, able-bodied men, to weep uncontrollably from pain. I think about what it means, in these days of concentrated amnesia in the US, for a church such as St. John the Divine to carve out spaces in which we can remember the body in pain: to invite the liturgies of other faiths, to share the pulpit with the Other; to invite difficult cargos. This is not a church that aims to use its monumental structure or its gilded beauty for forgetting. St. John’s asks: what does it mean for us to bear witness as a congregation? What does it mean for a place of worship to invite us to engage in “personal communion” with art that takes as risky journeys as does Alexander’s, to ask us to listen to the “still, small, voice within” during such perilous communions?

* * *

Inside St. John’s, friendly security guards and an official "welcomer" at a booth encourage a donation of $10 to the church, although one can walk in for free. St. John is a tourist destination, and is used to visitors. The space is so different from churches in Europe; here, the shadow spaces are soundchambers of noise, conversation, laughter, and congregational gregarity. An orchestra is practicing as I walk in: Violins are being tuned, a singer is doing scales, a conductor is directing sections of musicians and their instruments. Near the orchestra’s practice space, cello cases, sweaters and musicians’ bags are scattered on haphazardly scattered chairs. Although St. John’s is used to strangers, this is a place of long-established friendships. The benevolent security men in navy blue uniforms walk throughout the church, less on patrol than in conversation with visitors in the corridors.

Alexander’s work are adapted to each location. Her preference, she writes, in an email exchange, “is for site specific installation, out of museums and galleries,” and away from the “white cube” and its attendant commercial aspirations. She prefers her work to be shown “in social spaces” that have broader groups of witnesses in mind, rather than “elitist and specialized audiences.” She has shown work in chapels before, as well as on a beach, in a courtroom and the British Officers’ Mess room in the Castle of Good Hope (the fort first built by the Dutch arrivals in South Africa’s Cape of Good Hope). Alexander has presented her work in a Cathedral space on two previous occasions, the first also in Cathedral of St. John the Divine as part of the exhibition, Personal Affects (2004), and the second at the Galilee Chapel of Durham Cathedral, U.K. (2009), in the context of interdisciplinary research, “On Being Human,” organised by the Institute of Advanced Study at Durham University.

Alexander often references baboons, vultures and wild dogs. Many of the figures that make an entrance here have appeared in different arrangements and may not necessarily appear again as they do here, in “Surveys”, or in such a concentration. Such repetition – reappearances of the same "actors" who re-enact various scenes in different settings – reminds me that atrocity and amnesia happen repetitively, and in many places, with similar players. Alexander’s work has elements that might be seen as specifically speaking to South African and African history. Her work often includes industrial-strength gloves, machetes, sickles and earth. Placed together here, however, the different elements offer a different composite. The “Bushmanland earth” that I’ve seen used in other installations, for instance, evokes specificity – a specific geography, a certain set of historical events. But here, the iron ore’s brick red permeates the stained light and the sepulchral shadows of the church: The very air is bleeding in the chapel.

In Morningside Heights, Alexander’s work also feels less suggestive of South Africa’s story, and more evocative of the last five centuries here - of the genocide necessary for the myth of America, for creating the empty spaces of deciduous forest and marshland in which immigrants subsequently made their home. Here, her work reminds of more recent events: the unbearable spaces of damaged flesh, forever incarcerations and willful forgetting created by the twenty-first century’s oil wars. Manhattan is a place of forgetting, a location that uses suppression, selective memory, and avoidance through consumerism, aggressive responses as a means of sidestepping this blood-permeated history and present. It is a place in which one history is razed, only to build larger, more skyward-reaching monuments to power. These are the ways in which powerful nations sidestep horrendous histories of bloodletting, a cultivated amnesia common to both South Africa and the U.S.

For Alexander, “the Cathedral is a rather ideal space for [these reasons] and some of my concerns around and interest in faith and proselytism, and aspects of Christianity and its social role.” The exhibition’s curator, Pep Subirós, maintains that although Alexander’s decisions were “in frequent dialogue” with him, “and this dialogue sometimes modified her initial ideas,” the final decisions concerning the location and arrangement of the different artworks were Alexander’s – “not because she imposed” her ideas, he said, “but because the spatial context and its multiple symbolic elements inevitably play an important part in the final configuration, and it was part of the art project to decide the forms and the limits of this relation. These are decisions for which the artist, ultimately, has to take responsibility.” In fact, Subirós understands the “curator’s role in a solo show of a living artist” to be more “that of a ‘midwife’ assisting the artist’s efforts for the best possible delivery of her or his work,” rather than that of a director.

Jane Alexander, Infantry (Photograph by Mario Todeschini). Photo courtesy the artist.

Jane Alexander, Infantry (Photograph by Mario Todeschini). Photo courtesy the artist.

If you pay attention, you will see that Alexander and Subirós used elements specific to each chapel to interact with the stage-play world within each of the seven Chapels of the Tongues. In the St. Boniface Chapel, on an elevated red velvet carpet laid out for an arriving army, wild dog-men are arranged before the Cathedral’s monumental sculpture of St. Michael. They stand three rows wide and nine deep, the slim, muscular bodies marching forward on black booted feet, dog-faces turned in unison to the right. This army’s uniform dedication is to that rightward gaze, focus firmly set on the duty to which they assigned their bodies, to those orders controlling their actions. They remind me of the beauty inherent in Soviet-era display parades, and of the impossibility of countering the might of such power. But in front of them is a minuscule dog figure standing on all fours, feet planted in a pose that is both steady and ready for motion, gaze fixed clearly on its goal. This un-photogenic creature, unmighty as any defiant rabble-rouser, contains, in its taut, small body, the possibility of disruption. This figure, which can be so easily dismissed by the uniform rows of well-funded, well-trained armies, is the insurgent whose heart and mind no empire can win. One wonders if St. Michael will guide this cur to victory, or if the avenging warrior-angel is on the side of more conventional power.

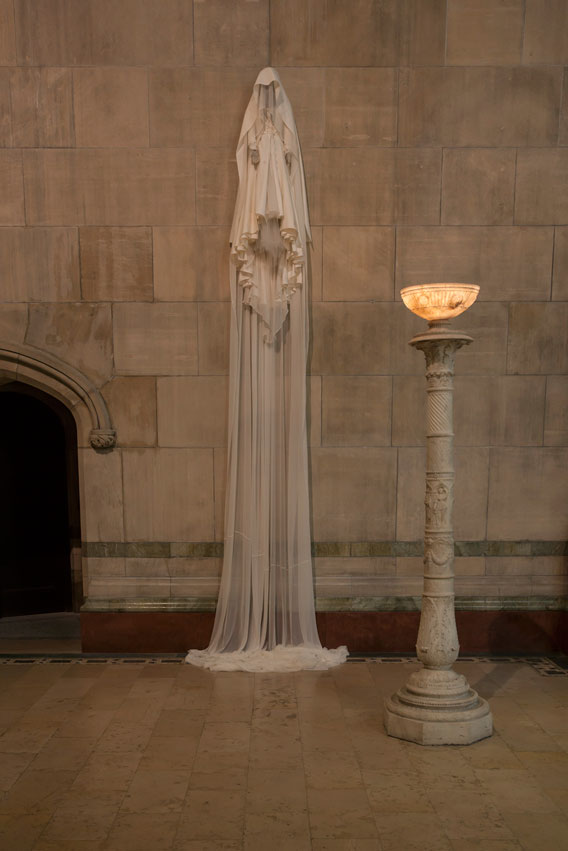

The Chapel of St. Saviour contains a familiar booted figure from a show I saw in Cape Town in 2010, with the sound of World Cup vuvuzelas trumpeting in my ear. This is a bleached-white Jesus figure, posed eternally atop the munitions box: arms outstretched, crucified. But this Jesus, replete with a decorative crown of thorns, has neither arms nor hands: Lifeless industrial-strength red gloves substitute for those appendages, hanging useless at the end of broomstick arms. Though he has come to save, to atone for sins, this Jesus’ hands are red-rubber clean, and red-rubber lifeless. Opposite, separated by a double row of chairs and a luminous clerestory window of stained glass, is an illuminated bridal figure. Layer upon layer of translucent ivory silk and white chiffon shroud the face, head, and body of the veiled wearer. The bridal train cascades to the floor of the chapel, pooling on the tile. This, the bride of Christ – the congregational body – is hung high on the chapel wall, far away from the unfocused gaze of our armless Christ-figure.

Jane Alexander, Lamb with stolen boots (Photograph by Mario Todeschini). Photo courtesy the artist.

Jane Alexander, Attendant (Photograph by Mario Todeschini). Photo courtesy the artist.

The North Transept of the church was gutted by a fire in 2001; there is no roof overhead, and the walls are marked by the damage inflicted by the fire. Some forgotten garden tools – a rake, spade, a rickety wooden ladder – are propped up in a corner. One feels vulnerable to the open air, and falsely protected by the remaining grey stone walls. In the open space of what used to be a chapel floor is Alexander’s “Security."(1) Here, Alexander has constructed an extraordinary montage: a double row of high chain-link fence topped with neat rolls of barbed wire, with scavenging bird-figures. In between the two rows of fencing is a foot-wide walkway scattered with sickles and machetes. These instruments are used to sustain life – tools commonly used for farming in regions without large machinery. That they can also eviscerate and erase entire populations of neighbors is not far from our minds. Scattered between these instruments are industrial-strength rubber gloves, the kind used for working with corrosive chemicals. Dirty from the rust bleeding out from the sickles and machetes, they are reminiscent of butcher’s gloves: It as if blood has stained an impervious material meant to resist and protect one from damage.

Jane Alexander, Security (Photograph by Mario Todeschini). Photo courtesy the artist.

Jane Alexander, Security (Photograph by Mario Todeschini). Photo courtesy the artist.

Within the enclosed rectangle is an immaculate, brilliant green lawn, inhabited by a lone, wingless vulture-figure - a stalking sentinel who cannot leave this protective enclosure. What Alexander has planted is not grass, but spring wheat. Evelyn Owen from the Museum for African Art in Manhattan tells me that the germination process, which involved soaking and leaving the seeds to rest, actually took three days before they were sown on this black rectangle of soil.(2) Now, that black rectangle, which had a millimetre of sprouting green on the day of the opening, is a carpet of luminescent springtime, attracting a scavenging city pigeon and a red-beaked common finch. The Security Vulture has not frightened them away. They are busy pecking at the stalks of green, plucking out entire clumps with black earth still attached to shallow roots. Surveying this scene – one that encloses in safety and entraps – is a watchful baboon-masked figure, its perfectly formed human fingers curled next to its foot, ensconced on a high ledge. Its gaze is fixed on far-away places.

* * *

It takes a lot of fearlessness to "be" with Alexander’s work. The first time I encountered her sculptures, I felt I had to stand with them in truth, with compassion – with the realisation that I will probably never understand that suffering, but that the stain of it is something I live under and together with. This is not "easy" work; these are not "pretty" sculptures, though they are obviously so beautifully made. Curators may feel skepticism about Alexander’s work precisely for those reasons – that people who come to see it in a gallery may neither sit with it and take the time to understand it, nor time to let their thoughts be with these figures, as they require. Adding to that art-world reluctance is Alexander’s reticence towards being a spokesperson for her work. She rarely gives interviews or agrees to being photographed. When she does speak, it isn’t as a recorded statement, but as a conversation. In an email exchange, she wrote that she is “hesitant” to give statements “in case it interferes with your response...Part of the value of that text for me is that it is a response to what was there, rather than to me or what I might say.”

If you engage with Alexander’s work, or write about it, you must walk in and walk away with how your narratives intertwined with what you felt as you encountered her work. That is, don’t go in with bullshit-speak. Don’t go there hoping to use art-world mumbo-jumbo as a prosthetic. Go there to engage with risk. Be real in the space of the sacred. For Americans who walk into this church - for people from this historic neighborhood, where the initial boatloads from the tail end of the nineteenth century gave way to dozens more – perhaps it is our trans-generational inheritance of the memory of displacement and suffering that enables us to engage with Alexander, full of fear, yes, for what her work will evoke, but grateful for communion with that small, hidden voice of history that helps us face our present with courage and conviction.

Endnotes.

(1) Alexander initially devised Security for the 2006 Sao Paulo biennial. Originally, the installation included the presence of a group of security guards. In later reproductions of the piece (for instance in the Goteborg Biennale (2006), but also Johannesburg (2009), Helsinki (2011), some times there have been security guards, sometimes not.

(2) Jeremy Johnston, who assisted with the design and installation, did the research for this particular installation. Alexander says that he “laboured mightily for the best possibility of wheat in erratic weather.”

This article was originally published on Africa is a Country.

M. Neelika Jayawardane is an associate professor of English at SUNY-Oswego. She was born in Sri Lanka, educated in a mining town in Zambia's Copperbelt Province and completed her university education in the US, at SUNY-Oswego. She teaches transnational memoirs and fiction connected to the immigrant and postcolonial experience, including contemporary Southern African and South Asian work. Her academic publications focus on the nexus between South African literature, photography and the transnational/transhistorical implications of colonialism and apartheid on the body. Her most recent publications include a review of critical texts on South African literature for the Journal of Commonwealth Literature and an essay on apartheid-era photography exhibit at the International Center for Photography in Manhattan for Art South Africa. She is a regular contributor to the online magazine Africa is a Country, and has been a regular visiting fellow at the Centre for African Studies in the University of Cape Town.