From a political and philosophical perspective, there is still much to flesh out conceptually on the importance of theatre, especially regarding the ways we might interrogate contemporary spectacles of violence through the lens of theatricality, performativity and the audience as witness. Rather than reducing “the theatre” to some fixed site for social congregation (with its evident class based privileges and modes of exclusion), borrowing from Michel Foucault, perhaps it is worth seeing the theatre as a “heterotopic space.” That is a site of many complex narratives – one where the sheer concentration of people’s attention allows for both the manufacturing of consent, along with subtle and no less creative forms of resistance. In this regard, we might see theatre as being much more than a place one goes to for a cultured experience, but instead as a complex assemblage where the lines between arts and politics, performance and ethics, pasts, presents and imagined futures are woven together.

Theatre remains under-theorized, despite its common appropriation in everyday discourse. I am not simply referring here to the ways in which the term theatre is often deployed to describe all manner of events, from sporting occasions to forms of protest, that display something of the carnevalesque, but how very real deployments of brutal force are framed by consciously appropriating theatrical discourse. I am evidently thinking here of the term “theatres of war.” Literary scholars no doubt appreciate the historical significance of this. Sophocles was, after-all, a military leader. And yet, in the contemporary period, it is precisely this aspect of the theatrical that allows for the organization, staging and enactment of all too real human crimes in ways that render, as Jacques Ranciere might point out, the audience as a mere passive spectator to a drama that is repackaged as entertainment and sold for public consumption. Simon Critchley is correct to argue there is an aspect to theatre that is complicit in the production of the most “monstrous illusions.”

My concern is to focus on a particular problematic that perhaps originates in theatre – what I have elected to term “a beautiful death”. Opera is an evident start point here as the term aptly describes the violence inflicted upon a sacrificial victim in ways that play directly into normalizing assumptions, most notably concerning the beautification of the (more often than not adulterous) female form. Puccini’s Butterfly is a most perfect and tragic embodiment of this. As mentioned, if we are however to make the case for more critical engagement with theatre, there is a need to broaden its applicability and engage more directly with the ways theatrical concepts have wider political and social resonance. This requires another engagement with the idea of a beautiful death, not only to further interrogate the recurring motif of a sacrificial victim, and how the death raises critical questions about who actually desires the killing? But how the concept also has a distinct politics insomuch as it marks out those lives that are ultimately disposable; while turning the brutality of violence into something that may be publically consumed by appealing directly to masculinized and militarized tropes.

Modern societies are saturated by images and representations of violence. From twenty-four hour news coverage, the extreme torture of Hollywood blockbusters, shock art and theatrical performance, to the increasingly brutal interactive gaming formats, the realities and resemblances of violence have arguably never been so embedded in our cultural, economic and social fabric. Some might even argue that violence saturation has become so normalized that it is reaching the point of the banal as its entertainment value supersedes any considered political and ethical questioning. Maybe not without coincidence, this comes at a time when social movements academics in the social scientists and the arts and humanities; along with and the art world more generally are facing considerable challenges as they try to respond to a broad spectrum of insecurities and vulnerabilities. Not only does this raise some searching pedagogical questions concerning the ways in which we are to teach about violence with a proper ethical care for the subject; it places new imperatives on how we might think about the different forms of representation, staging and performative enactments violence take.

It is worth pointing out here that in our mediatized age, those of us who live in sites of relative digitalized privilege are all bearing witness to acts of violence in one-way or another. Such witnessing is not, however, a neutral and objective process. What we “witness” is highly policed through aesthetic regimes of mediated suffering which prioritize the gaze by making us forced witness to historical events that appear beyond our control. Too often, in fact, the mediation of suffering through the formal qualities of beautification and design are presented as either cultural past times or matters of personal pleasure and taste rather than part of a broader engaged social-political discourse. If we are therefore to have a better picture of the cultured production of violence, there is a need to address the relationships between individual desires, representations of human suffering, humiliation and death as part of a wider economy of pleasure that is collectively indulged. What is more, there is a need to understand more fully those forms of poetic interventions that disrupt such aesthetics and reveal more critically the gendered, racial and class stakes. This raises two pressing questions: 1) How might we develop more ethically astute pedagogical practices that do justice to the subject? 2) And how might politics and philosophy respond better to challenge of violence by resourcing the poetic as expressed in the Arts?

In her widely celebrated book, Regarding the Pain of Others, Susan Sontag dealt specifically with the political function of violent aesthetics. As she noted, from the Spanish civil war onwards, the problem of violence has always been associated with the problem of re-presentation. When dealing with the problem of violence, we are then always dealing with the politics of aesthetics as representations and performances become integral to contested terrain of various truth-telling exercises – not least the attempts to authenticate “truths of war”. Robert Cappa’s now infamous The Falling Soldier was important in this regard.

Critically, for Sontag, what was striking about Cappa’s image was the way its 1937 publication in Life magazine turns the violent moment into something which both resembles a beautiful death, while affirming now all too familiar masculine and militarized qualities. The violence here is both domesticated and commodified as its publication would appear alongside an advertisement for Vitalis, a men’s hair cream product, as if to add a certain glamour to the portrait.

What is also striking about Cappa’s image is the way in which the last instant of the victim is captured so as to appear remarkably ballearic in its form. This reminds us of the American artist Robert Longo’s Men in Cities series.

Longo’s work is interesting for a whole number of reasons, not least the use of the Men in Cities portraits to adorn the walls in the New York apartment of Bret Ellis, the Wall Street killer from the movie American Psycho. In this particularly violent scene, the aestheticized background is mixed with the comic as the Killer dances to Huey Lewis and the News “Hip to be Square”, thereby rendering what ought to be an intolerable scene acceptable for public viewing.

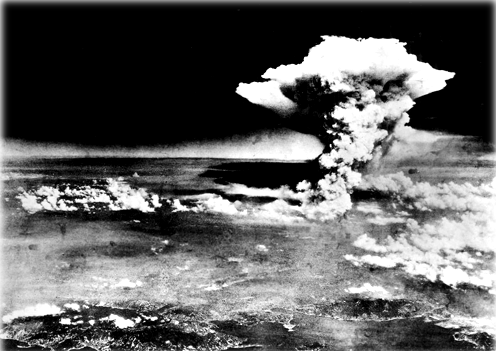

Since World War II, it has become common in many representations of mass atrocity to strip away anything of the human from the scene of the crime. Hiroshima & Nagasaki would invariably be a game changer in this regard. These events set in motion the erasure of the human from representations of mass violence in particular. This is what Hannah Arendt understood to be the triumph over metaphysics, as the technological ability to conquer terrestrial space, would render us increasingly remote from ourselves and the world in which we inhabit.

But even here we find the conscious attempts at a certain beautification. From the anointing of “Miss Atomic Bomb” in a Nevada beauty pageant, to the Life magazine (1946) image of U.S. Navy Vice Admiral William H. P. Blandy, his wife, and Rear Admiral Frank J. Lowry cutting a cake made in the shape of a mushroom cloud, it was clear that even the most abhorrent of human experiments could be aestheticized in such a way to render them tolerable for everyday public consumption.

But, of course, we know that every war produces its human casualties. Indeed, one of the seductions of war is embodied in the idea of the hero whose different order of sacrifice in the theatre of battle is often valorised as a “death well served”. In terms of sacrifice, the hero in fact proves to be the mimetic opposite of the visibly disposable. Both of which require a certain aestheticisation in order to validate the deathly sacrifice. There are a number of compelling Hollywood representations of this. Perhaps the more famous is the on screen killing of Sgt Elias from Oliver Stone’s Platoon that accompanied by Barbers Adagio for strings gestures towards the redemptive. This was a cinematic reworking of Art Greenspon’s photographic capturing of another last instant – this time in South Vietnam 1968.

This symbolic gesturing to the heavens to capture the essence of the military hero is replicated in the death of King Leonidas in the highly problematic and deeply Orientalising 300 the Rise of an Empire movie. Sacrifice thus speaking here in its performative silencing to forces that appear far greater than the individual who faces its mortal finitude, thereby staking through death a profound meta-physical claim.

The following clip from the 300 movie speaks volumes to our concerns here.

The opposite to a death well served – the beautiful death – in this particular movie becomes the deeply eroticised act of beheading with evident contemporary resonance – not least in terms of its intimacy and intolerability. Beheading serves a particularly disturbing aesthetic function here. It visibly destroys the singularity of the subject; while in the process denies them of a death without the sacrificial (thereby re-inscribing the importance of sacrifice and the death well served). As they are torn-away from their very humanity, the severed head also gestures towards a mere object, which can quite literally be thrown away!

So how might we counter these problematic representations of death? I would like to end by turning to the concept of the intolerable which Henry Giroux and myself have argued should be the site for rethinking the politics of aesthetics in the 21st Century. This however requires a fundamental reworking of the concept of intolerance in a more politically astute way so that we don’t simply fall back upon the questions of individual tolerances or wider issues of Sovereign protectionism and the regulated threshold between legal and illegal violence. We need to rethink the terms of intolerability in direct relation to the spectacle of violence such that we might make better ethical claims on the future as imagined in the present. Violence should be intolerable. That is the point. This requires us to counter the spectacle, exposing the limits of mediation that actually render violence tolerable for public consumption. It also requires is to rethink the relationships between violence, sacrifice and its beautification so that we might challenge the banalisation of violence, whilst actually opening a more affirmative discussion on what a beautiful death might actually entail?

Blog originally published in The Global Center for Advanced Studies' Blog.

Dr. Brad Evans is a political philosopher and critical theorist, whose work specialises on the problem of violence. The author of some ten books and edited volumes, along with over forty academic and media articles, he currently serves as a senior lecturer at the School of Sociology, Politics & International Studies, the University of Bristol, UK. His latest books include Disposable Futures: The Seduction of Violence in the Age of the Spectacle (with Henry Giroux, forthcoming, City Lights: 2015), Resilient Life: The Art of Living Dangerously (with Julian Reid, Polity Press, 2014), Liberal Terror (Polity Press, 2013), and Deleuze & Fascism (with Julian Reid, Routledge, 2013). He is currently working on a number of book projects, including Histories of Violence: An Introduction to Post-War Critical Thought (with Terrell Carver, Zed Books, 2015).